Introducing the Rational Speech Act framework

Chapter 1: Language understanding as Bayesian inference

Much work in formal, compositional semantics follows the tradition of positing systematic but inflexible theories of meaning. However, in practice, the meaning we derive from language is heavily dependent on nearly all aspects of context, both linguistic and situational. To formally explain these nuanced aspects of meaning and better understand the compositional mechanism that delivers them, recent work in formal pragmatics recognizes semantics not as one of the final steps in meaning calculation, but rather as one of the first. Within the Bayesian Rational Speech Act framework refp:frankgoodman2012, speakers and listeners reason about each other’s reasoning about the literal interpretation of utterances. The resulting interpretation necessarily depends on the literal interpretation of an utterance, but is not necessarily wholly determined by it. This move — reasoning about likely interpretations — provides ready explanations for complex phenomena ranging from metaphor refp:kaoetal2014metaphor and hyperbole refp:kaoetal2014 to the specification of thresholds in degree semantics refp:lassitergoodman2013.

The probabilistic pragmatics approach leverages the tools of structured probabilistic models formalized in a stochastic 𝞴-calculus to develop and refine a general theory of communication. The framework synthesizes the knowledge and approaches from diverse areas — formal semantics, Bayesian models of inference, formal theories of measurement, philosophy of language, etc. — into an articulated theory of language in practice. These new tools yield broader empirical coverage and richer explanations for linguistic phenomena through the recognition of language as a means of communication, not merely a vacuum-sealed formal system. By subjecting the heretofore off-limits land of pragmatics to articulated formal models, the rapidly growing body of research both informs pragmatic phenomena and enriches theories of semantics. In what follows, we consider the first foray into this framework.

Introducing the Rational Speech Act framework

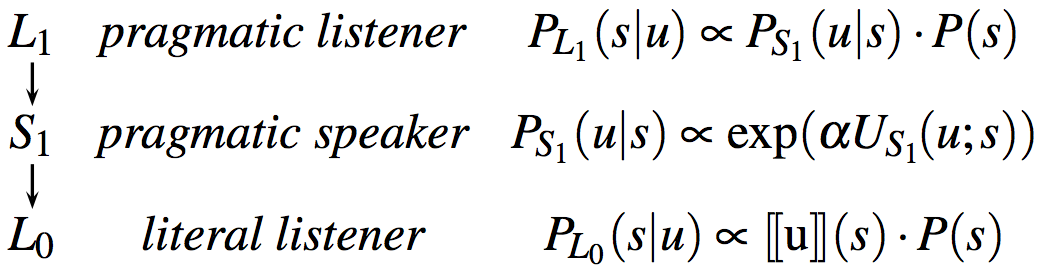

The Rational Speech Act (RSA) framework views communication as recursive reasoning between a speaker and a listener. The listener interprets the speaker’s utterance by reasoning about a cooperative speaker trying to inform a naive listener about some state of affairs. Using Bayesian inference, the listener reasons about what the state of the world is likely to be given that a speaker produced some utterance, knowing that the speaker is reasoning about how a listener is most likely to interpret that utterance. Thus, we have (at least) three levels of inference. At the top, the sophisticated, pragmatic listener, \(L_{1}\), reasons about the pragmatic speaker, \(S_{1}\), and infers the state of the world \(s\) given that the speaker chose to produce the utterance \(u\). The speaker chooses \(u\) by maximizing the probability that a naive, literal listener, \(L_{0}\), would correctly infer the state of the world \(s\) given the literal meaning of \(u\).

To make this architecture more intelligible, let’s consider a concrete example and a vanilla version of an RSA model. In its initial formulation, reft:frankgoodman2012 use the basic RSA framework to model referent choice in efficient communication. Let’s suppose that there are only three objects that the speaker and listener want to talk about, as in Fig. 1.

In a reference game, a speaker wants to refer to one of the given objects. To simplify, we assume that the speaker may only choose one property (see below) with which to do so. In the example of Fig. 1, the set of world states

\[S = \{\text{blue-square}, \text{blue-circle}, \text{green-square}\}\]contains the three objects given. The set of utterances

\[U = \{ \text{"square"}, \text{"circle"}, \text{"green"}, \text{"blue"} \}\]contains the four properties from which the speaker can choose.

A vanilla RSA model for this scenario consists of three recursively layered, conditional probability rules for speaker production and listener interpretation. These rules are summarized in Fig. 2 and will be examined one-by-one below. The overal idea is that a pragmatic speaker \(S_{1}\) chooses a word \(u\) to best signal an object \(s\) to a literal listener \(L_{0}\), who interprets \(u\) as true and finds the objects that are compatible with the meaning of \(u\). The pragmatic listener \(L_{1}\) reasons about the speaker’s reasoning and interprets \(u\) accordingly, using Bayes’ rule; \(L_1\) also weighs in the prior probability of objects in the scenario (i.e., an object’s salience, \(P(s)\)). By formalizing the contributions of salience and efficiency, the RSA framework provides an information-theoretic definition of informativeness in pragmatic inference.

Literal listeners

At the base of this reasoning, the naive, literal listener \(L_{0}\) interprets an utterance according to its meaning. That is, \(L_{0}\) computes the probability of \(s\) given \(u\) according to the semantics of \(u\) and the prior probability of \(s\). A standard view of the semantic content of an utterance suffices: a mapping from states of the world to truth values. For example, the utterance \(\text{"blue"}\) is true of states \(\text{blue-square}\) and \(\text{blue-circle}\) and false of state \(\text{green-square}\). We write \([\![u]\!] \colon S \mapsto \{0,1\}\) for the denotation function of this standard, Boolean semantics of utterances in terms of states. The literal listener is then defined via a function \(P_{L_{0}} \colon U \mapsto \Delta^S\) that maps each utterance to a probability distribution over world states, like so:

\[P_{L_{0}}(s\mid u) \propto [\![u]\!](s) \cdot P(s)\]Here, \(P(s)\) is an a priori belief regarding which state or object the speaker is likely to refer to in general. These prior beliefs can capture general world knowledge, perceptual salience, or other things. For the time being, we assume a flat prior belief according to which each object is equally likely. (As we move away from flat priors, we’ll want to revise these assumptions so that \(L_0\) (but not \(L_1\)!) uses a uniform prior over states. In fact, this is what reft:frankgoodman2012 assumed in their model. See Appendix Chapter 4 for discussion.)

The literal listener rule can be written as follows:

// set of states (here: objects of reference)

// we represent objects as JavaScript objects to demarcate them from utterances

// internally we treat objects as strings nonetheless

var objects = [{color: "blue", shape: "square", string: "blue square"},

{color: "blue", shape: "circle", string: "blue circle"},

{color: "green", shape: "square", string: "green square"}]

// set of utterances

var utterances = ["blue", "green", "square", "circle"]

// prior over world states

var objectPrior = function() {

var obj = uniformDraw(objects)

return obj.string

}

// meaning function to interpret the utterances

var meaning = function(utterance, obj){

_.includes(obj, utterance)

}

// literal listener

var literalListener = function(utterance){

Infer({model: function(){

var obj = objectPrior();

var uttTruthVal = meaning(utterance, obj);

condition(uttTruthVal == true)

return obj

}})

}

viz.table(literalListener("blue"))

Exercises:

- In the model above,

objectPrior()returns a sample from auniformDrawover the possible objects of reference. What happens when the listener’s beliefs are not uniform over the possible objects of reference (e.g., the “green square” is very salient)? (Hint: use acategoricaldistribution by callingcategorical({ps: [list_of_probabilities], vs: objects}). More information about WebPPL’s built-in distributions and their parameterizations can be found in the documentation.)- Try vizualizing the model output differently: call

viz.hist(literalListener("blue")), one of WebPPL’s visualization functions (WebPPL-viz discusses the various visualization options).

Fantastic! We now have a way of integrating a listener’s prior beliefs about the world with the truth functional meaning of an utterance.

Pragmatic speakers

Speech acts are actions; thus, the speaker is modeled as a rational (Bayesian) actor. He chooses an action (e.g., an utterance) according to its utility. The speaker simulates taking an action, evaluates its utility, and chooses actions based on their utility. Rationality of choice is often defined as choice of an action that maximizes the agent’s (expected) utility. Here we consider a generalization in which speakers use a softmax function to approximate the (classical) rational choice to a variable degree. (For more on action as inverse planning, see agentmodels.org.)

Bayesian decision-making

In the code box below, you’ll see a generic approximately rational agent model. Note that in this model, agent uses factor (other related functions are condition and observe, as documented here; for general information on conditioning see probmods.org). In rough terms, what happens is this: Each factor statement interacts with a call to Infer by incrementing a so-called log-score, the logarithm of the probability of the argument to be evaluated. For example, when Infer considers the probabilities of the three actions in the example below (by enumeration, its default method), it first calculates a log-score for each action (e.g., by evaluating the factor statement and considering the fact that each action is a draw from a uniform distribution), and then computes normalized probabilities from these. In effect, the function agent therefore computes the distribution:

// define possible actions

var actions = ['a1', 'a2', 'a3'];

// define some utilities for the actions

var utility = function(action){

var table = {

a1: -1,

a2: 6,

a3: 8

};

return table[action];

};

// define actor optimality

var alpha = 1

// define a rational agent who chooses actions

// according to their expected utility

var agent = Infer({ model: function(){

var action = uniformDraw(actions);

factor(alpha * utility(action));

return action;

}});

print("the probability that an agent will take various actions:")

viz(agent);

Exercises:

- Check to make sure

utility()returns the correct value fora3.- Explore what happens when you change the actor’s optimality parameter.

- Explore what happens when you change the utilities.

A rational speech actor

In language understanding, the utility of an utterance is how well it communicates the state of the world \(s\) to a listener. So, the speaker \(S_{1}\) chooses utterances \(u\) to communicate the state \(s\) to the hypothesized literal listener \(L_{0}\). Another way to think about this: \(S_{1}\) wants to minimize the effort \(L_{0}\) would need to arrive at \(s\) from \(u\), all while being efficient at communicating. \(S_{1}\) thus seeks to minimize the surprisal of \(s\) given \(u\) for the literal listener \(L_{0}\), while bearing in mind the utterance cost, \(C(u)\). (This trade-off between efficacy and efficiency is not trivial: speakers could always use minimal ambiguity, but unambiguous utterances tend toward the unwieldy, and, very often, unnecessary. We will see this tension play out later in the book.)

Speakers act in accordance with the speaker’s utility function \(U_{S_{1}}\): utterances are more useful at communicating about some state as surprisal and utterance cost decrease. (See the Appendix Chapter 2 for more on speaker utilities.)

\[U_{S_{1}}(u; s) = \log L_{0}(s\mid u) - C(u)\](In WebPPL, \(\log L_{0}(s\mid u)\) can be accessed via literalListener(u).score(s).)

Exercise: Return to the first code box and find \(\log L_{0}(s\mid u)\) for the utterance “blue” and each of the three possible reference objects.

With this utility function in mind, \(S_{1}\) computes the probability of an utterance \(u\) given some state \(s\) in proportion to the speaker’s utility function \(U_{S_{1}}\). The term \(\alpha > 0\) controls the speaker’s optimality, that is, the speaker’s rationality in choosing utterances. We define:

\[P_{S_{1}}(u\mid s) \propto \exp(\alpha U_{S_{1}}(u; s))\,,\]which expands to:

\[P_{S_1}(u \mid s) \propto \exp(\alpha (\log L_{0}(s\mid u) - C(u)))\,.\]The following code implements this model of the speaker:

// pragmatic speaker

var speaker = function(obj){

Infer({model: function(){

var utterance = utterancePrior();

factor(alpha * (literalListener(utterance).score(obj) - cost(utterance)))

return utterance

}})

}

Exercise: Check the speaker’s behavior for a blue square. (Hint: you’ll need to add a few pieces to the model, for example the

literalListener()and all its dependencies. You’ll also need to define theutterancePrior()— try using auniformDraw()over the possibleutterances— and thecost()function — try modeling it after theutility()function from the previous code box. Finally, you’ll need to define the speaker optimalityalpha— try settingalphato 1.)

We now have a model of the utterance generation process. With this in hand, we can imagine a listener who thinks about this kind of speaker.

Pragmatic listeners

The pragmatic listener \(L_{1}\) computes the probability of a state \(s\) given some utterance \(u\). By reasoning about the speaker \(S_{1}\), this probability is proportional to the probability that \(S_{1}\) would choose to utter \(u\) to communicate about the state \(s\), together with the prior probability of \(s\) itself. In other words, to interpret an utterance, the pragmatic listener considers the process that generated the utterance in the first place. (Note that the listener model uses observe, which functions like factor with \(\alpha\) set to \(1\).)

// pragmatic listener

var pragmaticListener = function(utterance){

Infer({model: function(){

var obj = objectPrior();

observe(speaker(obj), utterance)

return obj

}})

}

Putting it all together

Let’s explore what happens when we put all of the previous agent models together. In the following code, we assume that all utterances are equally costly (i.e., \(C(u) = C(u')\) for all \(u, u'\)) (see Appendix Chapter 3 for more on message costs and how to implement them).

// print function 'condProb2Table' for conditional probability tables

///fold:

var condProb2Table = function(condProbFct, row_names, col_names, precision){

var matrix = map(function(row) {

map(function(col) {

_.round(Math.exp(condProbFct(row).score(col)),precision)},

col_names)},

row_names)

var max_length_col = _.max(map(function(c) {c.length}, col_names))

var max_length_row = _.max(map(function(r) {r.length}, row_names))

var header = _.repeat(" ", max_length_row + 2)+ col_names.join(" ") + "\n"

var row = mapIndexed(function(i,r) { _.padEnd(r, max_length_row, " ") + " " +

mapIndexed(function(j,c) {

_.padEnd(matrix[i][j], c.length+2," ")},

col_names).join("") + "\n" },

row_names).join("")

return header + row

}

///

// Frank and Goodman (2012) RSA model

// set of states (here: objects of reference)

// we represent objects as JavaScript objects to demarcate them from utterances

// internally we treat objects as strings nonetheless

var objects = [{color: "blue", shape: "square", string: "blue square"},

{color: "blue", shape: "circle", string: "blue circle"},

{color: "green", shape: "square", string: "green square"}]

// prior over world states

var objectPrior = function() {

var obj = uniformDraw(objects)

return obj.string

}

// set of utterances

var utterances = ["blue", "green", "square", "circle"]

// utterance cost function

var cost = function(utterance) {

return 0;

};

// meaning function to interpret the utterances

var meaning = function(utterance, obj){

_.includes(obj, utterance)

}

// literal listener

var literalListener = function(utterance){

Infer({model: function(){

var obj = objectPrior();

condition(meaning(utterance, obj))

return obj

}})

}

// set speaker optimality

var alpha = 1

// pragmatic speaker

var speaker = function(obj){

Infer({model: function(){

var utterance = uniformDraw(utterances)

factor(alpha * (literalListener(utterance).score(obj) - cost(utterance)))

return utterance

}})

}

// pragmatic listener

var pragmaticListener = function(utterance){

Infer({model: function(){

var obj = objectPrior()

observe(speaker(obj),utterance)

return obj

}})

}

viz.table(pragmaticListener("blue"))

// unfold the following lines to see complete probability tables

///fold:

// var object_strings = map(function(obj) {return obj.string}, objects)

// display("literal listener")

// display(condProb2Table(literalListener, utterances, object_strings, 4))

// display("")

// display("speaker")

// display(condProb2Table(speaker, object_strings, utterances, 2))

// display("")

// display("pragmatic listener")

// display(condProb2Table(pragmaticListener, utterances, object_strings, 2))

///

Exercises:

- Explore what happens if you make the speaker more optimal.

- Add another object to the scenario.

- Add a new multi-word utterance.

- Check the behavior of the other possible utterances.

- Is there any way to get “blue” to refer to something green? Why or why not?

In the next chapter, we’ll see how RSA models have been developed to model more complex aspects of pragmatic reasoning and language understanding.

Table of Contents