Social reasoning about social reasoning

Chapter 9: Politeness

When using language, speakers aim to get listeners to believe the things that they believe. But sometimes, we don’t want listeners to know exactly how we feel. Imagine your date bakes you a batch of flax seed, sugar-free, gluten-free cookies before your big presentation next week. (What a sweetheart.) You are grateful for them—something to take your mind off impending doom. But then you bite into them, and you wonder if they actually qualify as cookies and not just fragments of seed glued together. Your date asks you what you think. You look up and say “They’re good.”

Politeness violates a critical principle of cooperative communication: exchanging information efficiently and accurately. If information transfer were the only currency in communication, a cooperative speaker would find polite utterances undesirable because they are potentially misleading. But polite language use is critical to making sure your date doesn’t charge out of the room before you can qualify what you meant by the more truthful and informative “These cookies are terrible.”

Brown and Levinson (1987) recast the notion of a cooperative speaker as one who has both an epistemic goal to correctly update the listener’s knowledge state as well as a social goal to minimize any potential damage to the hearer’s (and the speaker’s own) self-image, which they called face. Yoon, Tessler, et al. (2016) formalize a version of this idea in the RSA framework by introducing a new component to the speaker’s utility function: social utility.

A new speaker

The usual speaker utility from RSA is a surprisal-based, epistemic utility:

\[U_{\text{epistemic}}(u; s) = \log(P_{L_0}(s \mid u))\]Social utility can be defined as the expected subjective utility of the state the listener would infer given the utterance \(u\):

\[U_{\text{social}}(u; s) = \mathbb{E}_{P_{L_0}(s' \mid u)}[V(s')] = \sum_{s'} P_{L_0}(s' \mid u) \ V(s')\]where \(V\) is a value function that maps states to subjective utility values — this captures the affective consequences for the listener of being in state \(s\).

Speaker utility is then a mixture of these components:

\[U(u; s; \varphi) = \varphi \cdot U_{\text{epistemic}}(u;s) + (1 - \varphi) \cdot U_{\text{social}}(u;s)\]Note that at this point, we do not differentiate subjective state value to the listener from subjective state value to the speaker, though in many situations these could in principle be different. Also at this point, we do not allow for deception or meanness, which would be the exact opposite of epistemic and social utilities, respectively — though this could very naturally be incorporated. (In reft:yoonetal2016, they do investigate meanness by having independent weights on the two utilities. For simplicity, we adopt the notation of reft:yoonetal2017, in which they describe utility as a simpler mixture-model.)

In WebPPL, this looks like the following:

var utility = {

epistemic: literalListener.score(state),

social: expectation(literalListener, valueFunction)

}

var speakerUtility = phi * utility.epistemic + (1 - phi) * utility.social

expectation computes the expected value (or mean) of the distribution supplied to it as the first argument.

The second argument is an optional projection function, for when you want the expectation computed with respect to some transformation of the distribution (technically: a transformation of the support of the distribution).

Here, valueFunction projects the listener’s distribution from world states onto subjective

valuations of those world states (e.g., the subjective value of a listener believing the

cookies they baked were rated 4.5 out of a possible 5 stars).

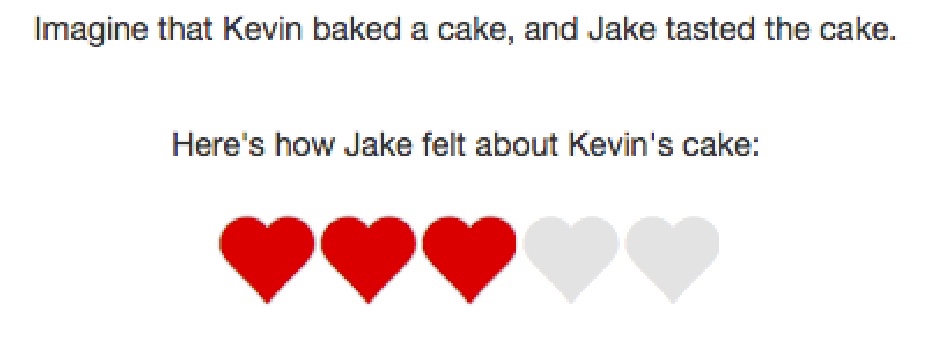

We consider a simplified case study of the example given at the beginning, shown in Figure 1 below. The listener has completed some task or produced some product (e.g., baked a cake) and solicits the speaker’s feedback. Performance on the task maps to a scale ranging from 1 to 5 hearts (shown below; cf. online product reviews). These are the states of the world that the speaker can be informative with respect to. Below, the speaker thinks the cake deserves 3 out of 5 hearts.

At the same time, these states of the world also have some inherent subjective value: 5 hearts is better than 3 hearts.

phi governs how much the speaker seeks to communicate information about the state vs. make

the listener believe she is in a highly valued state.

We start with a literal listener whose task is to interpret value judgments (e.g., “terrible,” “okay,” “amazing”) according to their literal semantics. The literal listener model assumed here is the exact same as in the vanilla RSA model of Chapter 1.

\[P_{L_{0}}(s\mid u) \propto [\![u]\!](s) \cdot P(s)\]var states = [1,2,3,4,5]

var utterances = ["terrible","bad","okay","good","amazing"]

// correspondence of utterances to states (empirically measured)

var literalSemantics = {

"terrible":[.95,.85,.02,.02,.02],

"bad":[.85,.95,.02,.02,.02],

"okay":[0.02,0.25,0.95,.65,.35],

"good":[.02,.05,.55,.95,.93],

"amazing":[.02,.02,.02,.65,0.95]

}

// determine whether the utterance describes the state

// by flipping a coin with the literalSemantics weight

// ... state - 1 because of 0-indexing

var meaning = function(utterance, state){

return flip(literalSemantics[utterance][state - 1]);

};

// literal listener

var literalListener = function(utterance) {

Infer({model: function(){

var state = uniformDraw(states);

var m = meaning(utterance, state);

condition(m);

return state;

}})

};

Exercise: Test the predictions of

literalListenerfor the various utterances.

Next, we add in the speaker, who reasons about the literal listener with respect to an epistemic and a social goal. The speaker model assumed here is exactly like in the vanilla RSA model of Chapter 1, except that we use a different (more complicated) utility function.

\[P_{S_1}( u \mid s, \varphi) \propto \exp \left ( \alpha \ U (s, u, \varphi) \right)\]// state prior, utterance prior, and meaning function

///fold:

var states = [1,2,3,4,5]

var utterances = ["terrible","bad","okay","good","amazing"]

// correspondence of utterances to states (empirically measured)

var literalSemantics = {

"terrible":[.95,.85,.02,.02,.02],

"bad":[.85,.95,.02,.02,.02],

"okay":[0.02,0.25,0.95,.65,.35],

"good":[.02,.05,.55,.95,.93],

"amazing":[.02,.02,.02,.65,0.95]

}

// determine whether the utterance describes the state

// by flipping a coin with the literalSemantics weight

// ... state - 1 because of 0-indexing

var meaning = function(utterance, state){

return flip(literalSemantics[utterance][state - 1]);

};

///

// value function scales social utility by a parameter lambda

var lambda = 1.25 // value taken from MAP estimate from Yoon, Tessler, et al. 2016

var valueFunction = function(s){

return lambda * s

};

// literal listener

var literalListener = function(utterance) {

Infer({model: function(){

var state = uniformDraw(states);

var m = meaning(utterance, state);

condition(m);

return state;

}})

};

var alpha = 10; // MAP estimate from Yoon, Tessler, et al. 2016

var speaker1 = function(state, phi) {

Infer({model: function(){

var utterance = uniformDraw(utterances)

var L0_posterior = literalListener(utterance)

var utility = {

epistemic: L0_posterior.score(state),

social: expectation(L0_posterior, valueFunction)

}

var speakerUtility = phi * utility.epistemic +

(1 - phi) * utility.social

factor(alpha * speakerUtility)

return utterance

}})

};

speaker1(1, 0.99)

Exercises:

- Describe the kind of speaker assumed by the above function call (

speaker(1, 0.99))?- Change the call to the speaker to make it so that it only cares about making the listener feel good.

- Change the call to the speaker to make it so that it cares about both making the listener feel good and conveying information.

- Change the value of

lambdaand examine the results.

A listener who understands politeness

If different speakers can have different weights on the mixture parameter phi, which governs the trade-off between kindness and informativity, listeners may have uncertainty about what kind of speaker they are interacting with. (Another motivation is to interpret the kindness vs. informativity behind a single utterance, for a known speaker.) This can be captured by endowing the pragmaticListener with a prior distribution over phi, corresponding to uncertainty about the parameter of the speaker’s utility function. The pragmatic listener model assumed here is a joint-inference model, much like those used in previous chapters, inferring world state and phi-parameter at the same time:

///fold:

var states = [1,2,3,4,5]

var utterances = ["terrible","bad","okay","good","amazing"]

// correspondence of utterances to states (empirically measured)

var literalSemantics = {

"terrible":[.95,.85,.02,.02,.02],

"bad":[.85,.95,.02,.02,.02],

"okay":[0.02,0.25,0.95,.65,.35],

"good":[.02,.05,.55,.95,.93],

"amazing":[.02,.02,.02,.65,0.95]

}

// determine whether the utterance describes the state

// by flipping a coin with the literalSemantics weight

// ... state - 1 because of 0-indexing

var meaning = function(utterance, state){

return flip(literalSemantics[utterance][state - 1]);

}

// value function scales social utility by a parameter lambda

var lambda = 1.25 // value taken from MAP estimate from Yoon, Tessler, et al. 2016

var valueFunction = function(s){

return lambda * s

}

// literal listener

var literalListener = cache(function(utterance) {

Infer({model: function(){

var state = uniformDraw(states)

var m = meaning(utterance, state)

condition(m)

return state

}})

})

var alpha = 10; // MAP estimate from Yoon, Tessler, et al. 2016

var speaker1 = cache(function(state, phi) {

Infer({model: function(){

var utterance = uniformDraw(utterances);

var L0_posterior = literalListener(utterance);

var utility = {

epistemic: L0_posterior.score(state),

social: expectation(L0_posterior, valueFunction)

}

var speakerUtility = phi * utility.epistemic +

(1 - phi) * utility.social

factor(alpha * speakerUtility)

return utterance

}})

})

///

var pragmaticListener = function(utterance) {

Infer({model: function(){

var state = uniformDraw(states)

var phi = uniformDraw(_.range(0.05, 0.95, 0.05))

var S1 = speaker1(state, phi)

observe(S1, utterance)

return { state, phi }

}})

}

var listenerPosterior = pragmaticListener("good")

// note in this case that visualizing the joint distribution via viz()

// produces the wrong joint distribution. this is a bug in the viz() program.

// we visualize the marginal distributions instead:

display("expected state = " +

expectation(marginalize(listenerPosterior, "state")))

viz(marginalize(listenerPosterior, "state"))

display("expected phi = " +

expectation(marginalize(listenerPosterior, "phi")))

viz.density(marginalize(listenerPosterior, "phi"))

Above, we have a listener who hears that they did “good” and infers how well they actually did, as well as how much the speaker values honesty vs. kindness.

Exercises:

- Examine the marginal posteriors on

state. Does this make sense? Compare it to what theliteralListenerwould believe upon hearing the same utterance.- Examine the marginal posterior on

phi. Does this make sense? What different utterance would make thepragmaticListenerinfer something different aboutphi? Test your knowledge by running that utterance through thepragmaticListener.- In Yoon, Tessler, et al. (2016), the authors ran an experiment testing participants’ intuitions as to the kind of speaker they were dealing with (i.e., inferred

phi). ModifypragmaticListenerso that she knows the speaker (a) wants the listener to feel good, (b) wants to convey information to the listener, and (c) both, and test the models on the utterance “good”.- The authors also ran an experiment testing participants’ intuitions if they knew what state of the world they were in. Modify

pragmaticListenerso that she knows what state of the world she is in. Come up with your own interesting situations (i.e., choose a state and an utterance) and show the model predictions. Are the predictions in accord with your intuitions? Why or why not?

Politeness with indirect speech acts

Above, we modeled the case study of white lies, utterances which convey misleading information for purposes of politeness. There are other ways to be polite, however. Speakers may deliberately be indirect for considerations of politeness. Consider a listener who just gave an objectively terrible presentation. They look fragile as they come to you for your feedback. You tell them “It wasn’t bad.”

Why would somebody produce such an indirect speech act? If the speaker wanted to actually be nice, they would say “It was fine.” or “It was great.” If the speaker wanted to actually convey information, they would say “It was terrible.” Yoon et al. (2017) and Yoon, Tessler et al. (2018) hypothesize that speakers produce indirect speech acts in order to appear to care both about conveying information and saving the listener’s face. Can we elaborate the model above to account for politeness by being indirect? First, we can define the speaker’s utility as we did before, breaking it up into component parts of epistemic and social utility, defined now with respect to the pragmatic listener \(L_1\).

\[U_{\text{epistemic}}(u; s) = \log(P_{L_1}(s \mid u))\] \[U_{\text{social}}(u) = \mathbb{E}_{P_{L_1}(s' \mid u)}[V(s')] = \sum_{s'} P_{L_1}(s' \mid u) \ V(s')\] \[P_{L_1}(s \mid u) = \int_\varphi P_{L_1}(s, \varphi \mid u) d\varphi\]where \(V\) is a value function from before that maps states to subjective utility values. With our higher-order speaker, however, we have a new possible utility component: a self-presentational utility – defined with respect to the pragmatic listener’s inferences about the politeness mixture component \(\phi\).

\[U_{\text{presentational}}(u) = \log(P_{L_1}(\varphi \mid u)) = \int_s P_{L_1}(s, \varphi \mid u) ds\]Speaker utility is then a mixture of these three components, weighed by mixture component vector \(\omega\):

\[U(u; s; \varphi; \omega) = \omega_{\text{epistemic}} \cdot U_{\text{epistemic}}(u; s) + \omega_{\text{social}} \cdot U_{\text{social}}(u) + \omega_{\text{presentational}} \cdot U_{\text{presentational}}(u)\]and the speaker model is simply a soft-max utility speaker:

\[P_{S_2}( u \mid s, \varphi ) \propto \exp \left ( \alpha' \left ( U(u; s; \varphi; \omega) \right ) \right)\]var speaker2 = function(state, phi, omega) {

Infer({model: function(){

var utterance = sample(utterancePrior)

var L1 = pragmaticListener(utterance)

var L1_state = marginalize(L1, "state")

var L1_phi = marginalize(L1, "phi")

var utilities = {

epistemic: L1_state.score(state),

social: expectation(L1_state, valueFunction),

presentational: L1_phi.score(phi)

}

var speakerUtility = omega.epistemic * utilities.epistemic +

omega.social * utilities.social +

omega.presentational * utilities.presentational

factor(alpha2 * speakerUtility)

return utterance

}})

}

The pragmaticListener model is the one defined in the case study above, a listener who reasons both about the true state and the speaker’s goals (specifically, phi). Now, we have a speaker (speaker2) who produces utterances in order to get the pragmatic listener to believe a certain true state, feel good, and think of the speaker as somebody with a particular utility trade-off phi. This latter goal is the “self-presentational component”. This component allows the speakers to say things that are literally false but also not directly signalling states with high subjective values. In other words, speakers can say false things and be indirect.

To look at indirectness, we will add utterances with negation, which are indirect insofar as they convey less information than their positive form (e.g., “not amazing” is potentially true of 1 - 4 hearts).

///fold:

var utterances = [

"yes_terrible","yes_bad","yes_good","yes_amazing",

"not_terrible","not_bad","not_good","not_amazing"

];

var states = [0,1,2,3];

var isNegation = function(utt){

return (utt.split("_")[0] == "not")

};

var cost_yes = 0;

var cost_neg = 0.35;

// in Yoon, Tessler, et al. (2020), the speaker optimality parameters were set to be the same value

var speakerOptimality = 4;

var speakerOptimality2 = 4;

var round = function(x){

return Math.round(x * 100) / 100

}

var weightBins = map(round, _.range(0,1, 0.05))

var phiWeights = repeat(weightBins.length, function(){1})

var cost = function(utterance){

return isNegation(utterance) ? cost_neg : cost_yes

}

// var uttCosts = map(function(u) {

// return isNegation(u) ? Math.exp(-cost_neg) : Math.exp(-cost_yes)

// }, utterances)

//

// var utterancePrior = Infer({model: function(){

// return utterances[discrete(uttCosts)]

// }});

// Parameter values = Maximum A-Posteriori values from Yoon, Tessler et al., (2018)

var literalSemantics = {

"state": [0, 1, 2, 3],

"not_amazing": [0.9652,0.9857,0.7873,0.0018],

"not_bad": [0.0967,0.365,0.7597,0.9174],

"not_good": [0.9909,0.736,0.2552,0.2228],

"not_terrible": [0.2749,0.5285,0.728,0.9203],

"yes_amazing": [4e-04,2e-04,0.1048,0.9788 ],

"yes_bad": [0.9999,0.8777,0.1759,0.005],

"yes_good": [0.0145,0.1126,0.9893,0.9999],

"yes_terrible": [0.9999,0.3142,0.0708,0.0198]

};

var meaning = function(words, state){

return flip(literalSemantics[words][state]);

};

///

var listener0 = cache(function(utterance) {

Infer({model: function(){

var state = uniformDraw(states);

var m = meaning(utterance, state);

condition(m);

return state;

}})

}, 10000);

var speaker1 = cache(function(state, phi) {

Infer({model: function(){

var utterance = uniformDraw(utterances);

var L0 = listener0(utterance);

var utilities = {

inf: L0.score(state), // log P(s | u)

soc: expectation(L0) // E[s]

}

var speakerUtility = phi * utilities.inf +

(1-phi) * utilities.soc - cost(utterance);

factor(speakerOptimality * speakerUtility);

return utterance;

}})

}, 10000);

var listener1 = cache(function(utterance) {

Infer({model: function(){

var phi = categorical({vs: weightBins, ps: phiWeights})

var state = uniformDraw(states);

var S1 = speaker1(state, phi);

observe(S1, utterance)

return {

state: state,

phi: phi

}

}})

}, 10000);

var speaker2 = function(state, phi, weights) {

Infer({model: function(){

var utterance = uniformDraw(utterances);

var L1 = listener1(utterance);

var L1_state = marginalize(L1, "state");

var L1_phi = marginalize(L1, "phi");

var utilities = {

inf: L1_state.score(state), // log P(s | u)

soc: expectation(L1_state), // E [s]

pres: L1_phi.score(phi) // // log P(phi | u)

}

var totalUtility = weights.soc * utilities.soc +

weights.pres * utilities.pres +

weights.inf * utilities.inf - cost(utterance);

factor(speakerOptimality2 * totalUtility)

var utt = utterance.split("_")

return {

"utterance particle": utt[0], utterance: utt[1]

}

}})

};

// Parameter values = Maximum A-Posteriori values from Yoon, Tessler et al., (2018)

display('Listener gives presentation, worthy of 0 out of 3 hearts ("truly terrible")...')

// informational

display("Speaker wants to give Listener accurate and informative feedback")

viz(speaker2(0, 0.5, {soc: 0.05, pres: 0.60, inf: 0.35}))

// social

display("Speaker wants to make Listener feel good")

viz(speaker2(0, 0.35, {soc: 0.30, pres: 0.45, inf: 0.25}))

// both

display("Speaker wants to make Listener feel good AND give accurate and informative feedback")

viz(speaker2(0, 0.35, {soc: 0.10, pres: 0.55, inf: 0.35}))

Exercises:

- What does the pragmatic listener infer when she hears “not amazing”? How does the pragmatic listener interpret the other “indirect” utterances?

- Write a purely informative

speaker2, who only cares about conveyingstate, but knows that the pragmatic listener will reason about bothphiandstate. Does it make different predictions from the model defined above?- Write a purely self-presentational

speaker2, who only cares about conveyingphi, but knows that the pragmatic listener will reason about bothphiandstate. Does it make different predictions from the model defined above?- Write an alternative

speaker2who, likespeaker1, is actually both kind and informative (as opposed to the self-presentational speaker model above). Does it make different predictions from the model defined above?

Table of Contents